The driving force behind my work was an internal need to investigate the side to my heritage which up until this point had been relatively unexplored. I am a quarter British, quarter Irish and half Caribbean. I became increasingly aware of my Caribbean roots in the wake of the Windrush scandal. My thoughts immediately went to my grandfather, a man from Trinidad who came to the UK on the Windrush ship in 1956. Although I have known my grandfather all my life, this project gave me a real opportunity to get to know his - and in turn my own - history better. Growing up with dual heritage, I knew I looked different, but I didn't necessarily feel different.

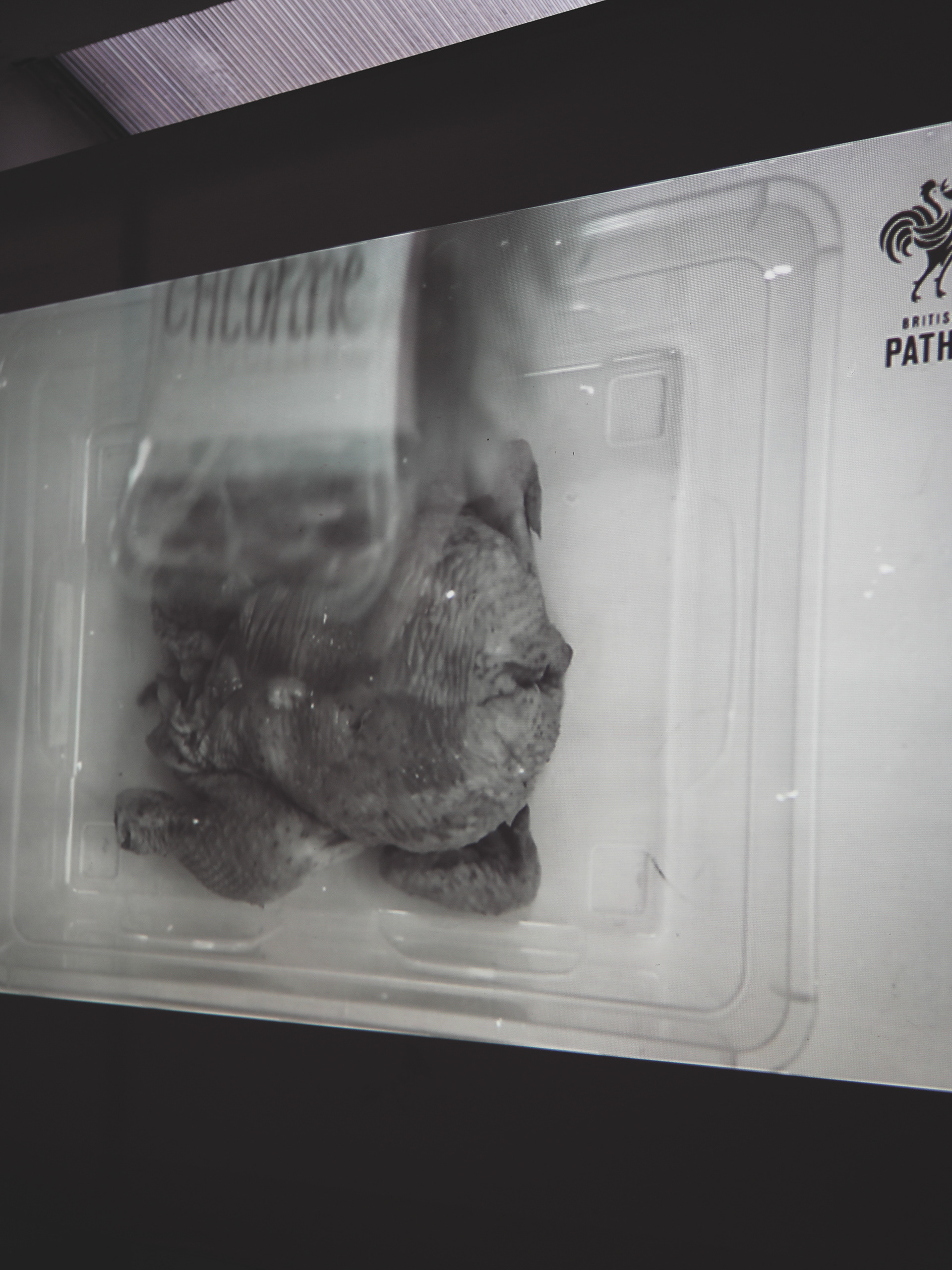

However, being dual heritage in a predominantly white country inevitably led to me being treated differently. Growing up I was aware of racism to an extent, but it is as I got older when I came to learn the backstory and context of the black experience in the UK. After Windrush, I thought of my grandfather, a man who came to Britain in order to help restore the country after the devastation of World War 2. I considered his experiences as a young man, invited to the 'mother country'. The name implies a nurturing and protective figure, but my grandfather's and so many of the Windrush migrants' experience was anything but. Prior to arriving in Britain, prospective migrants sang songs of jubilation and exuberance, but the commentary that followed after arrival were songs that carried a melody of pain with harmonies of disappointment. It was difficult to listen to my grandfather tell stories of rejection and racism in post-war Britain, especially considering his arrival in this country and the mixing of peoples in Manchester's newly formed cosmopolitan city was the reason I was born. Throughout my childhood, I had strong memories of my grandfather playing the steel pan instrument, and his attempts to get me to play too. At the time I did not fully appreciate the significance of the steel pan to him, but after interviewing him for this project, I see the importance now. For him, the pan was a source of solace in his hostile surroundings. It gave him an opportunity to form a close knit community amongst his Caribbean peers. It is for this reason that the steel pan is a cultural object of high status and significance amongst the Caribbean community. In itself it became an invaluable form of communication, a way for a marginalised group of people to express their culture where a prevailing white culture often strived to suppress the black voice. This project has been a crucial aspect of me developing and understanding the context of where my work sits within the contemporary art world. With parts of my own heritage being revealed, this project also echos the social cityscape of Manchester today. Many of the Windrush generation are still tackling the issues caused by the political scandal, however, in juxtaposition to this, we now see the cosmopolitan city of Manchester blossoming with diversity. As a result of inclusion within Manchester, black and white now exist alongside each other, with supportive black communities being formed in areas of Manchester. In this project I wanted to honour my grandfather's experience, and pay homage to all the Windrush migrants who toiled through unfair treatment, despite their contribution to the UK. I also want to glorify the steel pan, a cultural object which gave my grandfather his livelihood in this country and enabled him with opportunities to travel the country playing in bands, exposing many areas to the pan and in turn helping to solidify his belonging in Britain.